𝑮𝑨𝒁𝑬

""Oh that's just silly girl art,"" feat. Charlie Henzi

Is power interesting to you?

What about who’s seeing; whose gaze is whose?

As the landscape changes, some artists embrace technology, others embodiment. Some collide the two, play in the gauzy space between the body, the erotic, how it’s all enmeshed in social media as desire becomes inseparable from politics and commerce… this blurry edge that’s making voyeurs and pornographers of us all.

Charlie Henzi is one of them. An artist at the intersection of traditional techniques and modern image culture.

In this piece, Henzi’s voice is the only one you’ll read.

The gaze is yours.

— ULTRA

CHARLIE HENZI:

I've been seeing the same thing as you.

Artists going one way, galleries going another. Artists willing to meet in the middle; galleries saying I'll meet you in the middle too… but very few able to.

But art is something that I've just always loved. I’ve got a great aunt who was an art teacher, and always had projects for me. When she retired, she gave me all her materials — she was a big catalyst on just having access, access to ideas and different ways of working.

I’ve always been a collager, bringing together found materials, and composition has very much been my vibe.

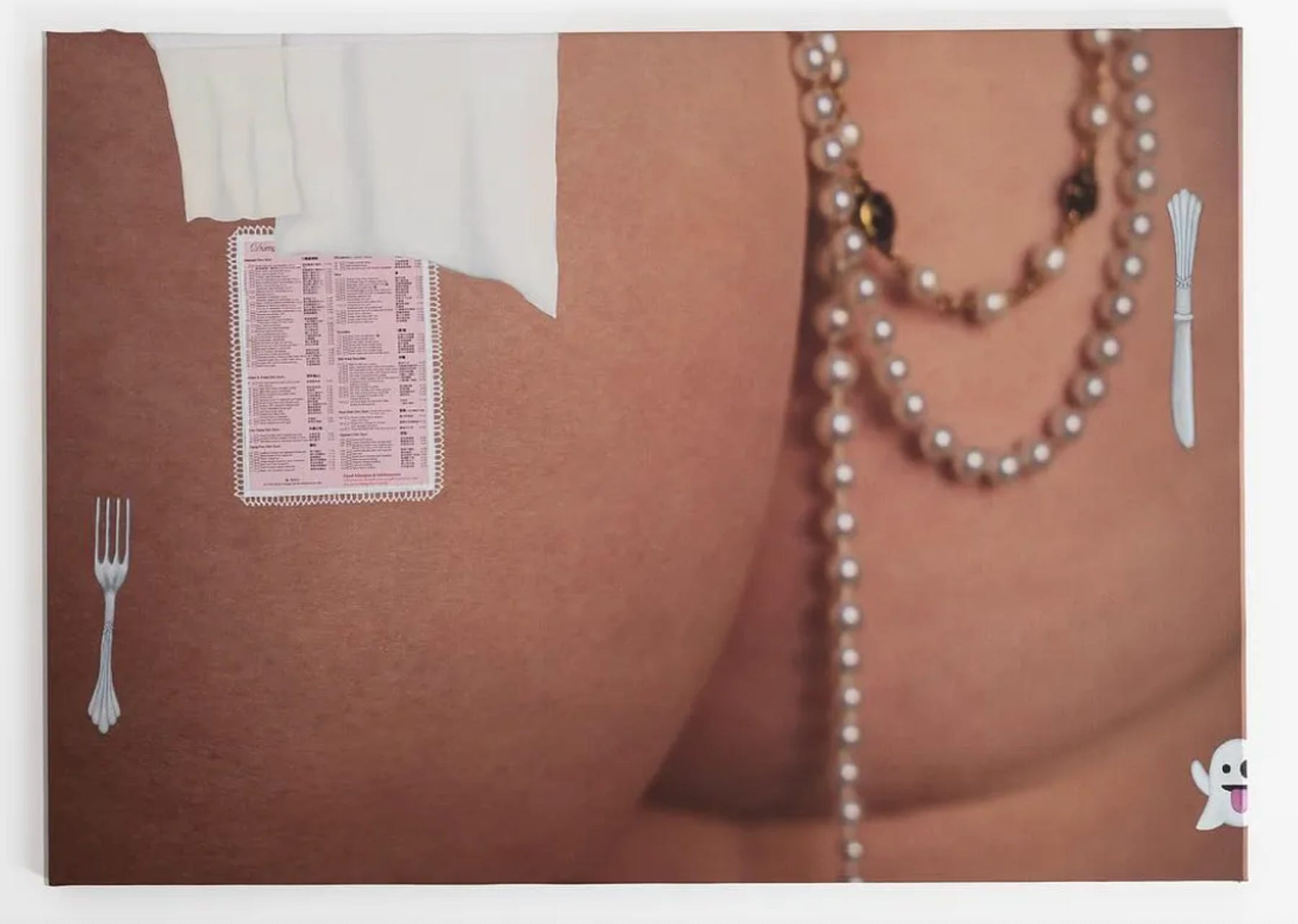

I really like working in one medium, but where it looks like something else. It does this little twist on the image, which makes you question the reality of the image or its purpose — for instance, working onto the fabric, they're taking photos, blurring them, turning them into fabric and canvases.

Ironically, the blurred image draws people in and then they see even less as they come closer, which I always find funny. It's not a painting, it's a photograph. Oh, I thought it was a painting. Oh, wait, it’s a photograph. So what actually is this image? Because in some of my work, you can tell. And some of it, you really can’t.

It helps put a little spin on things, particularly with what I’m trying to do and say about visual language and the gaze.

Whilst I make more painterly, canvas-based works, I love sharing a space with artists from ranging disciplines - someone whose practice is performance, sculpture, writing, archive-based…

It’s energising being around this intense mix of people who just care about the work and the art – compared to, say, the bubble that being around purely painters or a specific discipline can be (for me). It brings so many different approaches to the work and I love that.

The last four years has been a lot of playing around with different ways of working. But I seem to have settled on something sustainable. Something that I can store, transport... I can take them apart and redo them and they’d be safe. It's taken a long time to settle on a base technique that isn’t a headache to install and store. Focusing on a more ‘traditional’ way of working has pushed me to think about it in different ways. How can I play with it, change it? How can I fit all the ways I want to work and make into this medium?

A lot of the recent stuff on my Instagram I'm calling diary works; the product of my obsession with image culture and how visual language and visual codes have been inherently part of our world for the last few decades and what this means.

People make assumptions. I was bleach blonde in recent years, and seemed to be pigeon-holed into this one area; making these, quote-unquote diary works, a day in the life and people going, oh, it's just silly girl art.

Often, any female artist being interested in feminist art, particularly younger female artists — if they’re interested in social media in some way or take inspiration from that, you end up almost being seen as part of the silly influencer crowd with no depth. This is no hate on influencers, but the way it is often perceived and viewed – women doing anything often ends up having a negative twist of silly and inconsequential. And this is something I explore in my work.

Especially when you look at contemporary image culture over the last few decades, and how so much is sexualised especially within advertising – it is so driven by desire, want, fantasy, the (particularly) male gaze. And that doesn’t even include porn, which is the uber, extra-exaggerated, contorted version of it all. As an artist, you end up getting a little pushed into, you're a female artist and you look at porn on social media – oh we know how this goes.

What is it about it I find compelling?

I’ve written about the appropriation of the male gaze.

The male gaze is often something that’s projected onto a subject — but the appropriation of the male gaze is the idea that if you use the visual language of the male gaze aesthetic and vocabulary and play into it, then it’s protective, because you can hide behind the image that you’re putting forward. Or use it as a mask, a tool – it can be empowering; it doesn’t have to be seen as a passive protective measure. Maybe it is a proactive counter-move: when someone looks at you, and they're only seeing what you want them to see, it’s very much playing into codes and putting on a face, which is explored in a lot of my work.

I’ve had a lot of comments on how in my work, the composition is directly in front of the audience, a triangle of composition comes out of the canvas and includes the viewer in the art. Compared to, say, Baroque art where the composition is in a triangle with the figures interacting with each other in the piece and the audience looks on, but isn't part of it. Though my work still compositionally interacts within itself, as if it were on a stage. The audience may or may not realise how in viewing the curated piece, they bring their own meaning to it, it is set up for them. Forcing the viewer into a first person gaze becomes a mirror for their projections. The ambiguity is a form of control and power.

People seem to love decoding or trying to decode what these images are and what they mean in relation to each other, adding all this depth to something that might be simple. It draws on people’s fantasises, desires, anxieties, their gaze and perspective. But that’s how people project onto women and make assumptions based on whatever image they (women) try to or even aren’t trying to project of themselves. That is how the gaze works.

I've always been interested in images around porn: who's making it, but also who's seeing it.

But no matter what you do, you end up getting put within the male gaze, or you almost always end up getting pigeon-holed into that female artist stereotype. How can I change this power dynamic in a way that isn't necessarily obvious to everyone?

The stereotypical male gaze is sometimes only ever going to see what it wants to see, so it doesn’t see that it is actually not in a position of power in that situation.

That creates tension for some people viewing my work. Maybe they want to feel more comfortable or they want to be respectful — often they’re not sure if they are allowed to find it funny.

I don't want to make work that's purely commercial. I'm doing everything I can to stay away from that.

But at the same time, this is my career.

This conflict of opinions was a driving force for my interest in the gaze, and how people view me or my work, why I do certain things both in my life and in my art. It drove me to think about perceptions and really dig into visual codes and language.

This new way of working and being super obsessed with really getting into contemporary image culture and how people see and read, has definitely been part of kind of me going, well, I want to make work that I could sell, but I do not want to make work that will sell, if that makes sense. I have found that being an artist in today’s climate is a constant assessment and reassessment of where you stand and how you stand on this topic. I want to try to stay true to what I feel is right for myself.

I’m most interested in art that treads the line between conceptual and accessible, commercial and academic. Art that has commercial potential, rather than art that is purely commercial or that is so academic it becomes inaccessible to a wider audience.

I feel that playing with the gaze, perceptions, visual codes and language, and contemporary image culture does that for me – and I hope it does that for others.

There are some artists working today I particularly love.

Louise Reynolds creates these beautifully textured drawings in traditional mediums with titles taken from current news topics — when I first encountered them I was completely transfixed by the magic and depth of them. Her work does an amazing job at commenting on the absurdity and surreal nature of how the media world puts very contrasting stories side by side - major wars and celebrity affairs - by pairing her skill and use of traditional materials with this content. It produces work that is able to capture the myriad of conflicting natures within the media and how it feels for viewers.

Eva Dixon creates paintings, but works in so many materials more than paint. She pushes techniques - from different ways of installing, to gorgeous transparent or opaque canvases that have got springs and carabiner clips and you can see all the inner workings. They are unbelievably gorgeous. There is a wave of re-evaluating how artistic processes are defined especially with the rise of technology being so involved with art, and I think Dixon’s work is a perfect example of how painting as a medium is re-expanding in exciting ways.

Charlie Henzi is a British/American artist living and working in London. She graduated from the Royal College of Art with an MA in Contemporary Art Practise in 2024. She is fascinated by images of women in popular culture, the gaze, the performed female, consumption and consumerism. After studying visual codes and language for years, she now creates works that draw directly from this and her personal experiences, that comment on the current zeitgeist.

.

.

.