𝙃𝒂𝙣𝒅𝙢𝒂𝙙𝒆 / 𝑴𝙖𝒄𝙝𝒊𝙣𝒆𝙢𝒂𝙙𝒆

Fine art fabrication, feat. Mikey Ting

About a year ago,

— no wait, three months… I forget that time moves differently for me, that a day of mine is like a month of yours —

you might remember me standing in front of a piece by Jemima Lucas, a melted curtain of vinyl bound to a contorted metal stand and thinking to myself—

maybe this is what a painting is now.

You ever feel something like that?

Because I was with Mikey Ting then, and as we looked at it he began to verbally disassemble its component parts, talking through its construction, the stresses on the metal, pulling the thing apart, reverse engineering its method; what kind of fasteners were used, the skill required to drape it so precisely…

This was around the time I stopped looking in galleries for all the interesting work. When I was growing bored of chi-chi red wine art events and their polite posturing, thinking that some pieces, often the most exciting, ought instead to be discovered and dug up from the dirt.

We’re in an age of miracles, good and bad. Sometimes that means tech-poets drawing beautiful phantasmagoria from binary code, and other times it is raw craft gradually attained through years of rigour and traditional practice.

When I ask Mikey about his own approach he tells me it is about choosing to handle more and more of his own process, to see himself as artisan and artist, a creator who is capable of mass-producing concepts.

I like to have my hands touching everything I make.

Mikey is not a traditional artist, and demonstrates to me that, among other things, the future of fine art is fabrication.

T͟E͟C͟H͟N͟I͟Q͟U͟E͟S͟ ͟O͟F͟ ͟M͟A͟S͟S͟ ͟P͟R͟O͟D͟U͟C͟T͟I͟O͟N͟

The first time we met, the piece of his that had caught my eye was More Is More, a philosophy close to my heart of course.

(I mean… the focus of this journal is 𝔞𝔯𝔱 𝔢𝔵𝔱𝔯𝔢𝔪𝔦𝔰𝔪… it’s called ULTRA for fuck’s sake).

Joshua Citarella talks about the shape of the post-internet artist and although the traditional trajectory still has its place — especially if you have rich parents lel — institutional supremacy has been shaken by culture and technology and money.

The most inspiring artists I know deal with this dispassionately, without preciousness. They do not ponder and regret, but look around at the tools and materials available to them, that come to their hands, turn dirt into fuel.

I’m an engineer at heart with an artistic creative brain, not the other way round.

Being around industrialisation and machinery and production made me see these things not as distractions but opportunities.

They open up the possibility of expedited, efficient, economical practice.

Explain?

Consider the hidden costs of art-making.

The cost of studio space, of canvas, the cost of paints, of raw materials. The more I move into contemporary fine arts, the more my engineering skillset helps. It allows me to be more thoughtful, to consider when fabricating a piece: what is the cheapest, most efficient way to do that? Maybe it‘s to make fifty. After all, if I can make one, I can make a hundred thousand.

There’s a grittiness in the making of art, a down-to-earth, pragmatic core that everyone knows but rarely gets much airtime. Budgeting and form and transportation and storage. The logistics of magic. These can be material considerations; they can be bodily too, or immaterial — I think of the performance artists who long for quiet spaces with the right sprung flooring, venues to experiment without surveillance.

These aren’t mundane matters: they make the work.

Ting’s trajectory is to constantly learn — working with metal, mastering new tools, or deconstructing machines. Each skill becomes part of a larger vocabulary, piecing together what it means to make something wholly, deeply, and without relying on a single discipline.

But there are barriers. Practitioners with incredible knowledge can often gatekeep their techniques, perhaps fearful that these will get into the wrong hands, or be exploited at their expense. Arcane knowledge is lost when traditions aren’t passed down. You know how they say, no one really knows how to code anymore? New programmers are simply building on layers that are disconnected from the machine’s true language. We’re not creating, we’re renovating, and one day we’ll also be building in the ruins.

M͟A͟K͟E͟ ͟S͟O͟M͟E͟T͟H͟I͟N͟G͟ ͟H͟U͟M͟A͟N͟ ͟A͟G͟A͟I͟N͟

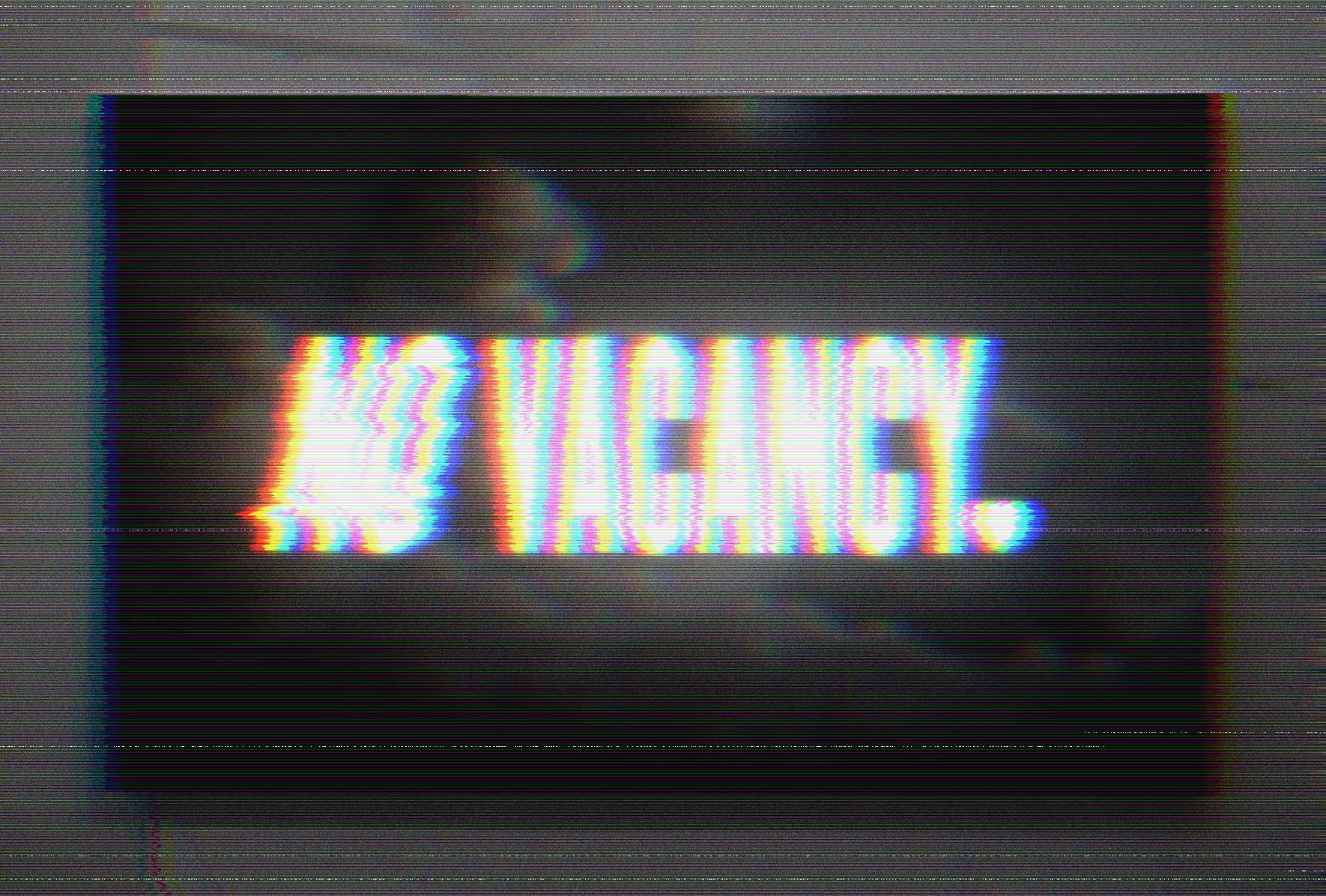

Nominally, I told Mikey I wanted to write something about his piece for MACHINE DREAMS at Goodspace Gallery, even though it feels like a stepping stone to the kind of work that is just around the corner in his career. It fits: the brief was “AI art” and No Vacancy is a response that is resolutely not an AI piece of work.

But that wasn’t it, really. Mostly I was interested in understanding the role of a hand-making artist in a world increasingly defined by the commodification of creation: where content streams from endless digital pipelines. Whether with the commoditisation of creation on offer, what Citarella calls the moodboard-industrial complex, whether it was already being dragged through the dirt, ready to be sanitised and yassified by the VCs and tech bros, like they did with weed.

My response to machine art is to go deeply human and fabricate something that feels like it shouldn’t be made by hand.

At its best there is a subversive sense I want to provoke a response, a heady combination of futurism and nostalgia. But also the subversion of such physicality, materiality, smell.

He’s not worried about AI replacing his craft; his focus is on deep hand work that feels machined, the combination of tactile synthetic materials, and in the future, organics like skin and leather. Something deeply human and primal.

Ultimately, they’re all just tools. But Midjourney is still not a good enough tool for what I’m trying to achieve. It’s like a welder with not enough amperage; a hammer without enough weight; like using a carpenter’s hammer for a smithing job. The job is harder to do correctly.

So. In a handmade practice that is heavily reliant on machinery, on technology, with experimentation in technology… it’s the maker that centres it all. Not just with taste, but also with craft.

Mikey tells me about a friend of his who buys defunct, decayed technology and repurposes it; robotics parts and arms from decayed machines, repurposes them for new uses —

But as any process expands, generally there are human hands being replicated. Human hands calibrate the machines. Human brains calculate something different.

The work you write about in ULTRA centre deeply human experiences in response to things which might be embedded in technology.

Even in engineering, nothing happens without a human being.

…

Mikey Ting is a Chinese-Kiwi multidisciplinary artist working in Naarm (Melbourne).

His work draws on an extensive knowledge of materials, styles and craftsmanship.

.

.

.

Go further:

love this. so many thoughts see word vomit below

'his focus is on deep hand work that feels machined' - I like to frame code like this too. Seeing the artists hand in code. The deep hand work in interfacing with machines

The line of thought in this article also reminds me of the hacker manifesto...

a lot of contemporary art feels like an exercise in augmentation and with this I wonder how this augmentation is reversed and if humans then become the final frontier of encryption and somehow augment the machines

Seems like art is like a melting pot to reflect how little machines are without the human hand...

“My response to machine art is to go deeply human“: yes, yes, yes 🙌 me too!