I almost lost my sight this week.

Lying in the fading light, images of eyes loomed large in my head.

As a teenager, I remember an art teacher showing me parts of Un Chien Andalou. A razor blade put to an eyeball… its images erupted violently in my mind like what - the fuck - am I looking at?

I love a world where art can do that, where casual snuff doesn’t just appear on your Twitter timeline, but is crafted in glorious hyperreality.

There’s a squeamishness to eyes, the idea of them being touched, poked, prodded, having stuff poured in them, having them cut; the weird combination of their solidity, their ability to see infinite worlds, and yet, still… fragile, squishy and weird.

There’s plenty of horror to eyes. I always remembered Bataille’s Story of the Eye — when I first read it years ago it had a similar effect — connecting the gaze indelibly to voyeurism… to look and to desire, to take what you want; and for an eye to be penetrated, or broken apart like an egg. When I revisited it recently, I found it a little flat; milk is for the pussy, kids raping kids — maybe I’m just getting jaded or too old, but it was all a little… on the nose.

Dali & Hitchcock created wonders of the subconscious, an elaborate dream sequence in Spellbound that unlocks the central mystery within a world of eyes. As he sleeps he solves the crime; a perfect synergy of waking and dream.

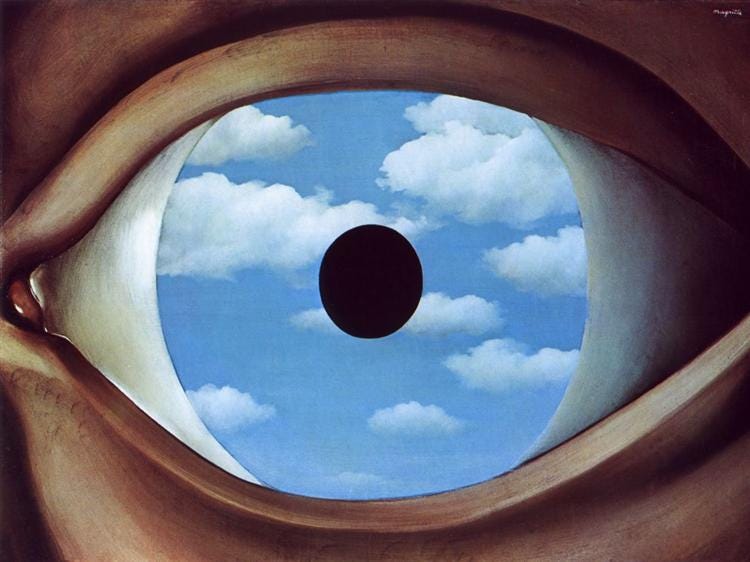

So dive in. Magritte thought of an eye as The False Mirror; surrealists loved eyes for their capacity to see into the inner world, an entry point to the subconscious. And also for their capacity — writ large, vast, unseeing — to unnerve.

Faced with the prospect of losing both eyes, or only one, I took encouragement from a lineage of blind creators — Homer, Milton, Kahlo, Joyce, Goya, Borges… Makers who still wished to live, to see new possibilities, even if they couldn’t see. Borges’ quote, on losing his sight, Now I can live my dreams with less distraction.

I remembered my father, whose own loss of sight left him in a half-world for years, perpetually uncertain what was real, and what was imagined.

Maybe it all was, or nothing.

Maybe I should have listened more closely to the stories he told of the things he saw.

I read, through blurring sight, Tara Heffernan, the blind art historian who writes about fine works with humour and humanity.

I sat, in endless hospital waiting rooms, listening to gorgeously textural soundscapes, wondering if I would still get to see any of my favourite sights —those faces, places, objects most precious to me — and for how long. If I might look upon them one last time before the light fades.

A friend who explained why she was so content with a seemingly unsuitable lover:

He sees me.

A favoured uncle who, whenever you tell him it’s nice to see him, will always reply:

It’s nice to be seen.

What does it really mean to see?

.

.

.